Overlooked is a series of obituaries about remarkable people whose deaths, beginning in 1851, went unreported in The New York Times. This month they adding the stories of important L.G.B.T. figures.: this a REPRINT of one of them ROBERTA COWELL

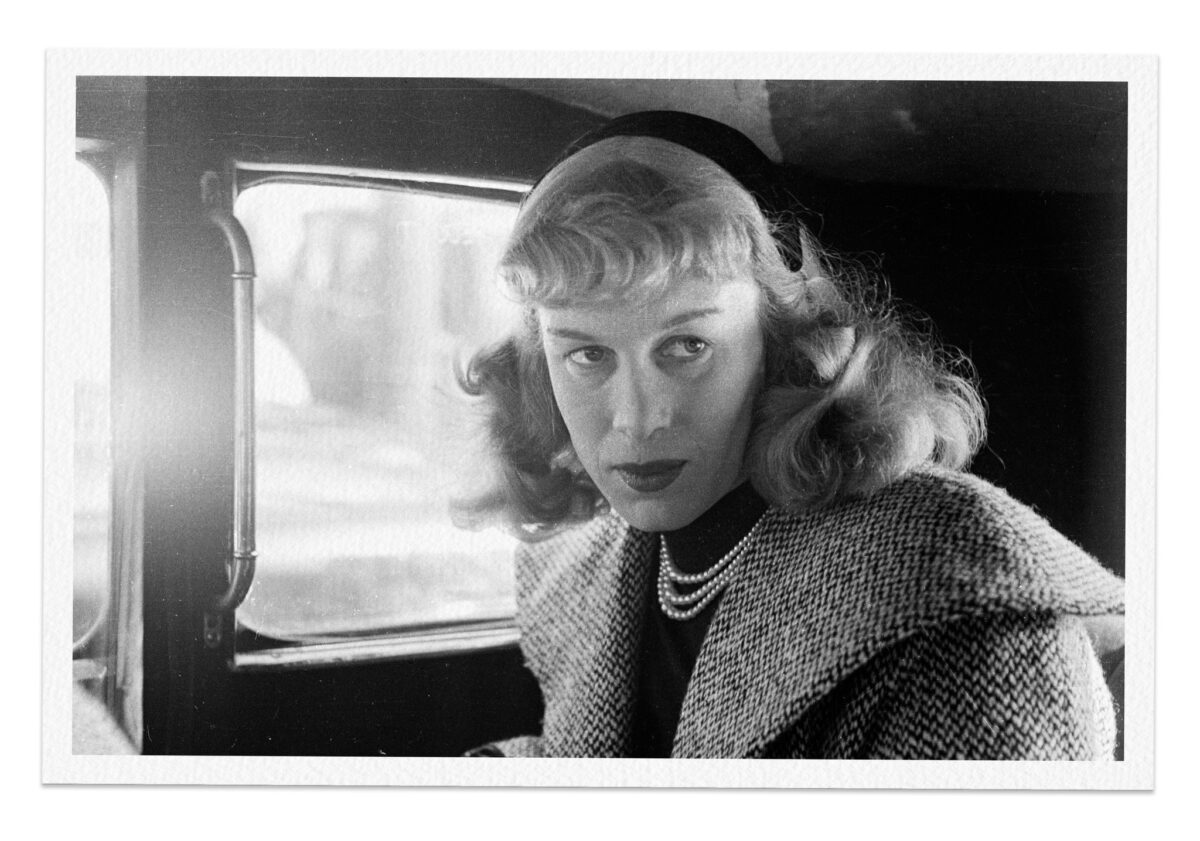

At the height of Roberta Cowell’s celebrity status, in 1954, her face adorned the cover of Britain’s popular Picture Post magazine. When her story appeared in a newspaper, “I received 400 proposals. Some of them of marriage,” she said in an interview for The Sunday Times of London in 1972. “I could have had titles, money, the lot.”

She achieved this fame when she became the first person in her country known to have her gender reassigned from male to female. Her transition — and all of the yearnings and hopes that came with it — involved hormone treatments and surgeries despite what some regarded in strait-laced 1950s Britain as flouting contemporary laws.

“Since May 18th, 1951, I have been Roberta Cowell, female,” she pronounced in her autobiography. “I have become woman physically, psychologically, glandularly and legally.”

Americans were perhaps more familiar with Christine Jorgensen, a former U.S. Army clerk who transitioned in Denmark just months after Cowell. When Jorgensen died of cancer in 1989 at 62, the event was recorded in an obituary in The New York Times.

Cowell’s death, by contrast, went all but unremarked upon, even in Britain. Her body was found on Oct. 11, 2011, in her small apartment in southwest London by the building superintendent. A handful of friends attended her funeral, but, apparently at her request, there was no fanfare for the woman who had helped pioneer gender reassignment at a time when it was virtually taboo.

Only in 2013 — two years after her death — was her passing reported, by the British newspaper The Independent on Sunday.

“So complete was her withdrawal from public life that even her own children did not know she had died,” the article said.

Cowell wrote in her autobiography “Roberta Cowell’s Story,” that during their meeting, over lunch, Dillon revealed that he had himself changed his gender identity through doses of testosterone and gender-affirming surgery.

Together they agreed that he would help her transition by performing a procedure that was prohibited under so-called “mayhem” laws, forbidding the intentional “disfiguring” of men who would otherwise qualify to serve in the military. If discovered, Dillon would almost certainly have been prevented from completing his studies to become a physician. The operation, thus, was conducted in great secrecy, and its success enabled Cowell to seek medical affidavits to have her birth gender formally re-registered as female.

Soon afterward, Cowell became a patient of Harold Gillies, a pioneer of plastic surgery who had performed gender-affirming surgery on Dillon, according to the book “The First Man-Made Man: The Story of Two Sex Changes, One Love Affair, and a Twentieth-Century Medical Revolution” (2006).

Soon afterward, Cowell became a patient of Harold Gillies, a pioneer of plastic surgery who had performed gender-affirming surgery on Dillon, according to the book “The First Man-Made Man: The Story of Two Sex Changes, One Love Affair, and a Twentieth-Century Medical Revolution” (2006).

“If it gives real happiness,” Gillies wrote of his procedures, “that is the most that any surgeon or medicine can give.”

By several accounts, Dillon fell deeply in love with Cowell, but she ultimately rejected his proposal of marriage.

From an early age, she wrote, she felt conflicted about her gender, compensating for feminine “characteristics” with an “aggressively masculine manner” that persuaded gay men to take her “for one of themselves.”

Physically, she was sensitive about being overweight, displaying what she called “feminoidal fat distribution.” In her teenage years, other pupils nicknamed her “Circumference” and “Bottom.” She left school at 16 to work briefly as an apprentice engineer until she joined the Royal Air Force in 1935. Her ambition was to become a fighter pilot, but she was found to suffer from acute airsickness and was deemed “permanently unfit for further flying duties with the R.A.F.”

From then until the start of World War II in 1939, she studied engineering at University College London and entered a series of automobile races including the Antwerp Grand Prix in Belgium. She enlisted in the Army in 1940.

In 1941 she married Diana Margaret Zelma Carpenter, a fellow engineer and racecar driver whom she had met in college. They had two daughters, Anne and Diana. They separated in 1948 and divorced in 1952.

Despite her earlier dismissal from flying duties, Cowell was allowed to return to the R.A.F. in 1942, flying combat and aerial reconnaissance missions in Spitfires and other aircraft. After the Allied D-Day landings in Normandy in June 1944, she flew out of a Belgian air base in a Hawker Typhoon airplane that was shot down by ground fire over Germany on a low-level attack east of the Rhine River. The flight, she said, had been scheduled as the “very last trip of my second tour of operations.” In fact it was her last flight of the war.

Fearing that her captors would treat her harshly, she twice sought to escape and twice she failed. She was transferred to Stalag Luft I, a prison camp for Allied aircrews in north Germany near the Baltic Sea between Lübeck and Rostock.

In her autobiography, she described the surreal elements of wartime life, relating perilous adventures with ironic detachment. She spoke of blacking out at 40,000 feet when her oxygen supply malfunctioned but somehow reviving after her plane plummeted almost to the ground. And, on another occasion, she recounted making an emergency landing atop a cliff on the English coastline just as her plane ran out of fuel.

In the early days of her captivity, she said, an Allied air raid on Frankfurt forced her and her captors into a bomb shelter where angry German civilians realized that she was an enemy pilot. She persuaded them “in my halting German” that she was not a bomber pilot and told them the untruth that her mother and father had been killed in a German raid on London. “It seemed to do the trick and the angry growling died down,” she wrote in her autobiography. “I wonder what would have happened to a Luftwaffe pilot discovered in an air-raid shelter during the blitz.”

Conditions at Stalag Luft I worsened as the end of the war approached, with Soviet Red Army troops advancing across Germany toward Berlin. Food supplies were so meager, she wrote, that inmates ate stray cats raw and she lost 49 pounds. In May 1945, as German forces surrendered, their captors abandoned the facility, leaving it unguarded until Soviet troops liberated it. Within days, Cowell and other British captives had been flown home aboard American Flying Fortress bombers.

The immediate postwar years confronted Cowell with the practical problems of earning a living, variously building and racing cars and renovating houses to sell at a profit. But she also detected a mounting sense of “restlessness and unhappiness,” she wrote in her autobiography, and resolved to undergo Freudian psychoanalysis. “It became quite obvious that the feminine side of my nature, which all my life I had known of and severely repressed, was very much more fundamental and deep-rooted than I had supposed.”

She began to live a double life, taking hormone treatments to enhance her femininity while still living as a man.

Then came the turning point when she met Dillon. The encounter was “so shattering that the scene will be crystal-clear in my memory for the rest of my life,” she wrote.

Then came the turning point when she met Dillon. The encounter was “so shattering that the scene will be crystal-clear in my memory for the rest of my life,” she wrote.

After three years of therapy and surgery, Cowell seemed to find emotional contentment that was matched only intermittently by material security. Two business ventures, in experimental car engineering and women’s clothing, did not survive.

The publication of her story in Picture Post in 1954 and her autobiography earned her the equivalent of several hundred thousand dollars. In 1957 she won a noted hill climb auto race and bought a wartime Mosquito fighter-bomber in which she planned to break the speed record for a flight across the South Atlantic. But the attempt never came about. In 1958 she appeared in bankruptcy court where she said she had no assets and significant debts, owed mainly to her father.

Cowell’s name has been summoned as a trailblazer in the years since her death, her transition having preceded by decades the public discourse over gender identity and L.G.B.T.Q. rights.

Perhaps because she was one of the first to transition medically, she didn’t recommend it easily to others, saying, “Many of those people will regret the operation later. There have been attempted suicides.”

Whether her views would have changed over time will never be known; in 1972 she said she was writing a second autobiography, but it was never published.

After World War II, she developed an interest in the idea of a combination of hormone therapy and surgery to more closely align her body with her gender identity. This had been reinforced by a book called “

After World War II, she developed an interest in the idea of a combination of hormone therapy and surgery to more closely align her body with her gender identity. This had been reinforced by a book called “