Circle & Star Theatre, Hampstead

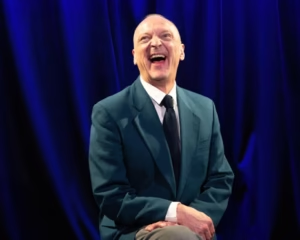

David Benson returns with his legendary portrait of the outrageous comedy star in My Life with Kenneth Williams

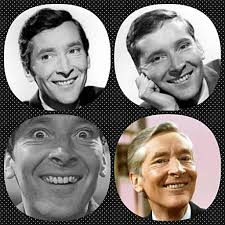

When I was a child, Kenneth Williams was one of the characters I most looked forward to on television. He was a household name, a national treasure. Yes, immortalised by the Carry On films—but also a regular fixture on the intelligent and fascinating ‘talk shows’ of the past (Parkinson, Wogan, Aspel) back when they really were talk shows: uninhibited conversation rather than dutiful or even desperate plugs for a new book or film. Williams himself often reminded us that “the key to good conversation is a lack of inhibition,” and he lived by it.

As a child, I felt I knew him. His coarseness, his working-class background, his effeminacy—and more than that, though I was far too young to articulate it, his queerness. My own sixth-sense told me we were the same. I learned slowly. The fact that he was adored by my family made him a safe idol to cherish. Closeted gay men of that era became masters of hiding in plain sight: double entendres, flamboyance turned up to eleven, secret languages spoken loudly. Williams was exemplary at this.

The similarities didn’t end there. Kenneth famously sent himself up for his “spastic colon,” a condition that would ultimately contribute to his tragic death after an overdose of painkillers taken to numb the agony of a stomach ulcer. Meanwhile, the men in my family never stopped moaning about their bowels, their “undercarriage” (as my grandmother called it), or their toilet trouble. All martyrs to their arses and their lower regions. Seemingly, we were all in the same boat.

So, when I was invited to review David Benson’s My Life with Kenneth Williams, persuasion was not required.

The show opens with Benson performing Williams reading a surreal children’s story about oysters—hilarious, odd, and strangely touching. We soon learn that this story was recorded by the BBC for Jackanory, but was never actually broadcast. Regardless, it’s a brilliant way into Williams’ strange position straddling two worlds. He appeared on Jackanory more times than almost anyone (beaten only by Bernard Cribbins—make of that what you will), yet he remained a working-class figure navigating institutions designed for the comfortably middle-class and above.

Benson has great fun skewering the old BBC hierarchy: working-class kids watching ITV (if they even had a television) whilst the BBC was considered the preserve of the “right sort”—or the aspirational lower-middle classes desperately modelling themselves on those with money, status and cultural authority. Williams, surreally socially mobile back then in a way that is almost unimaginable now, sat mostly comfortably holding court but sometimes awkwardly in the middle of it all.

Benson has great fun skewering the old BBC hierarchy: working-class kids watching ITV (if they even had a television) whilst the BBC was considered the preserve of the “right sort”—or the aspirational lower-middle classes desperately modelling themselves on those with money, status and cultural authority. Williams, surreally socially mobile back then in a way that is almost unimaginable now, sat mostly comfortably holding court but sometimes awkwardly in the middle of it all.

Benson tells us that making people laugh at school saved him from being bullied for being “a Mo” (short for hoMosexual). When his story was finally accepted by the BBC in 1975—the year I was born—he hoped it might gain him popularity at ‘secondary modern’ in his home city of Birmingham. But when he discovered that Kenneth Williams was to be the narrator, his heart sank. There was no pride in camp then. Misogyny was so ingrained that the worst insult a boy could receive was to be likened to a girl.

My Life with Kenneth Williams is not so much a show but a séance, a bringing back of the dead, with David Benson as the medium. What follows is a pitch-perfect recreation of school life: a head teacher, a school pianist, and a painfully enthusiastic communal rendition of All Things Bright and Beautiful. The smell of the polished wooden floors comes flooding back. Suddenly, there is the memory of chalk dust and plimsoles and being made to strip to our underwear for PE lessons. The fear of being made to stand up for chewing or getting the words wrong sends shivers down the spine. The audience—largely white-haired—gamely participates, though I couldn’t help noticing the conspicuous absence of young queens there to celebrate their history. We are chastised repeatedly for getting the singing wrong, before the head teacher moves briskly on to announcing Benson’s BBC success—followed immediately by a “lecture” on bullying that amounts to telling us that anyone complaining of being bullied at school should keep their mouths shut and learn to stand on their own two feet. Such was the authoritarian and egregious standard of education at the time—it thinking it was doing what needed to be done ‘for our own good’.

Throughout the performance, Benson’s facial articulation is astonishing. His face seems to become malleable, almost sculptural like clay—conjuring not only Williams (the waspish nose, the flaring nostrils) but a whole parade of national treasures: Harry Secombe, Frankie Howerd, even Dame Maggie Smith, with whom Williams shared a close friendship until his death in 1988. It’s mimicry, yes—but rooted in observation and affection rather than parody.

In the second half, the show darkens. Benson reflects on his regret at not embracing Kenneth Williams more fully while he was alive—a feeling shared by many gay men whose internalised homophobia led them to wish the overtly flamboyant few would “butch up” instead of spoiling it for the others. One of the most compelling sequences takes place in a restaurant, where Williams is by turns charming, cutting, brittle and cruel. In a virtuosic monologue, Benson/Williams skewers a waiter, his friends, and a table of loud Americans — before the mood turns unmistakably sour. We see how that darkness intensified when Williams was alone, particularly in his home on Marchmont Street in Bloomsbury, directly opposite what is now the LGBTQ+ holy grail: Gays the Word bookshop.

Kenneth Williams was a complex figure, beloved by an entire nation, and My Life with Kenneth Williams is a story for everyone. It feels like a marriage consummated by Benson — someone who, like me, saw himself reflected in Williams’ impossible balancing act of identity. Illogically, perhaps, it deserves an even wider queer audience, and I suspect Benson will instinctively make space for those joining the dots later, those who weren’t there the first time round.

All of which is to say: if you grew up with Kenneth, regardless of sexuality, gender, age or ethnicity—you should see this show. Take a trip in Benson’s time machine. This is part of our history. And if you’re queer and unfamiliar with Kenneth Williams’ life and work, you should absolutely go. It will show you how people can be twisted, misshapen and hollowed out by ‘the closet’—and why that bastard door must be taken off its hinges for good.

Otherwise, I’m afraid your ‘queer wisdom card’ may have to be revoked.

As you were.

Justin David is the publisher at Inkandescent. He is also the author of Tales of the Suburbs, and The Pharmacist. www.inkandescent.co.uk Justin David is the publisher at Inkandescent. He is also the author of Tales of the Suburbs, and The Pharmacist. www.inkandescent.co.uk |

Leave a Reply