80 percent of gay men sent to the notorious Nazi concentration camp died there – some finding love among the horror or saving the lives of others first. That’s worth remembering this Holocaust Memorial Day (27 January).

Words: Hugh Kaye for Attitude UK

This is an updated version of this article. With thanks to Dr Anna Hájková and her research into the queer history

of the Holocaust for University of Warwick, and as previously published in German newspaper Tagesspiegel.

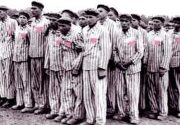

Adolf Hitler planned a 1000-year Reich. It lasted all of 12 years but in that short time, some 100,000 gay men were arrested. About half of them were sent to prison but as many as 15,000 were deported to concentration camps. By 1945, more than 40,000 such camps were in operation, and homosexuals were sent to any number of them.

But a relatively small number were sent to the most notorious of them all: Auschwitz.

Of the 97 gay men known to have been sent to Auschwitz, 96 were German. Scholars have unearthed the fate of 64 of them: 51 died in the camp. That’s 80 percent; a higher number than any other category of “undesirable” except for Jewish deportees.

Construction of a second camp began in October 1941. This was Birkenau which was to become the Nazis’ major killing center and the largest cemetery in the world. A third camp, known as Monowitz opened a year later. German companies, in particular IG Farben and Buna, set up factories here, using inmates as slave labor.

Unlike Jews and Roma, gay men were not as a rule sent direct to Birkenau. They were not, as such, marked for immediate death. However, they suffered unusually cruel treatment in the concentration camps, not only from the SS – they had their testicles boiled off in water and were given the most dangerous and arduous work under the Extermination Through Work program – but also from fellow prisoners who saw them as the lowest of the low. They were isolated, and every attempt that they made at contact with other prisoners brought them under suspicion of “initiating promiscuous relations.”

Little wonder that the rate of suicides among gay men was much higher than for any other category of prisoner. Throughout the whole concentration camp system, it was at least 10 times higher and there’s no reason to believe it would have been any lower at Auschwitz. And that figure is probably a conservative one, given that the Nazis didn’t always bother to register such deaths.

It is known that on 20 January 1942, there were 22 gay men in the main camp, and by August that year, there were 28 of them in the entire Auschwitz complex.

But some gay men were Jewish as well and their fate was often decided by whether they arrived at the camp wearing the yellow star of David (for Jews) or the almost-as-notorious pink triangle that homosexuals were forced to sew on to their clothes.

Fredy Hirsch was an athlete and PE teacher. He was Jewish and gay. He was born in Aachen, Germany, in 1916. He moved to Czechoslovakia to escape Nazi persecution, living with his lover Jan Mautner, a slightly older medical student, between 1936 and 1939 – as reported by Der Tagesspiegel.

Fredy organized and ran youth camps and looked to help young Jews hoping to emigrate to Palestine. When the Nazis invaded Czechoslovakia in 1939 and banned Jews from public places, Hirsch found a playground where the youngsters could still exercise and 18 of his youngsters managed to escape to neutral Denmark.

He was sent to Theresienstadt concentration camp, a place the Germans called the “model ghetto,” at the end of 1941. Mautner was deported there a few months later. Hirsch immediately began looking after a group of children, making sure they exercised and, more importantly in the squalid conditions, stayed clean, even holding hygiene competitions.

All the children were forced to work and Fredy tried to ensure they had “easier” jobs such as in the vegetable fields. He, of course, spoke German and this helped to forge reasonable relations with the guards even though he was Jewish and openly gay. On occasion, this helped him to remove children from transports from Theresienstadt to the death camps.

However, he pushed his luck too far, and having tried to make contact with a group of young new arrivals at Theresienstadt, he was sent to Auschwitz in September 1943 in a transport with 5,000 others – 300 of whom were 15 years old or younger.

However, he pushed his luck too far, and having tried to make contact with a group of young new arrivals at Theresienstadt, he was sent to Auschwitz in September 1943 in a transport with 5,000 others – 300 of whom were 15 years old or younger.

Fredy ended up in a “family camp” within Birkenau. It was usual for children not to be sent straight to their deaths but somehow Fredy became the children’s carer. He ensured they had lessons, organized activities and managed to get better food and warmer barracks for them. He even managed to persuade guards to hold the daily roll call inside rather than have the youngsters standing for hours in the freezing cold. But Fredy was not immune from hardship and on at least one occasion was viciously beaten when one of the children slept through the roll call.

Another transport of 700 children arrived at Birkenau in December 1943 – along with Jan Mautner, although he never saw Fredy again. Hirsch persuaded the authorities to allocate a second barracks for the younger children, those between the ages of three and eight so that they could put on a performance of Snow White for the SS.

Within the family camp, the mortality rate after the first six months was about 25 percent – in Hirsch’s barracks, there were almost no deaths at all.

Fredy soon became part of a resistance movement within the camp and learned that a large group of the children was to be gassed. Although it is not known for sure what happened next, it is thought Hirsch refused to be parted from his young charges despite his status a work-fit man meaning he would have likely been spared death. Some scholars think he took his own life via an overdose – or that Jewish doctors induced an overdose themselves in order to prevent him from causing an uprising that could have jeopardized their own lives. What is sure is the children were murdered on the night of 8 March 1944 and their bodies burnt. Fredy’s body was cremated on the same day. He was 28.

One of the survivors of the family camp in Theresienstadt said: “There was no one who was so self-sacrificing, [or] devoted to the children.” And although, he was airbrushed out of history by the communists in Czechoslovakia and some survivors after the war because of his homosexuality, in 2016 the Lord Mayor of his hometown in Aachen described him as “one of the most important sons of the city, if not the best known.”

One of the survivors of the family camp in Theresienstadt said: “There was no one who was so self-sacrificing, [or] devoted to the children.” And although, he was airbrushed out of history by the communists in Czechoslovakia and some survivors after the war because of his homosexuality, in 2016 the Lord Mayor of his hometown in Aachen described him as “one of the most important sons of the city, if not the best known.”

And Czech musician Zuzana Růžičková, who worked as a teacher’s assistant at the children’s barracks at Auschwitz, credited Hirsch with saving her life. He told her to lie about her age, saying she was 16 because younger children usually went straight to the gas chambers.

Many years later, she helped organize a monument for him. At the dedication, she said: “We hope that when the last of us who knew him have passed away, future generations will stand before this tablet and say: ‘He must have been a good, brave and beautiful person.”

Fredy’s partner Jan survived Auschwitz, as well as at least one other camp and being shipped back to Theresienstadt. He became a doctor and found a new partner. But he did not escape unscathed: he had contracted tuberculosis in the camps and died in Prague in 1951.

Kitty Fischer was 17 when she was sent to Auschwitz in 1944 because she was Jewish. On arrival, she was sent to have her head shaved. Terrified and bemused, she met a portrait painter from Munich. They made him clean the toilets seven days a week, 10 hours a day “as a better use of his brush.”

Seeing, his pink triangle, Kitty asked what it meant. When he said he was gay, she didn’t understand. He explained that he was a homosexual. Kitty had no idea what the word meant and asked whether it was a religion, which made the young man, who’d been sent to the camp with his partner in 1940, laugh.

Sometime later, the man brought her and her sister two hot jacket potatoes. He continued to smuggle food to Kitty every day. “He contributed to my survival, that is a fact,” she said.

The artist approached her again a month later. He was being moved to another camp and warned her that there was to be a selection the next day, when the Nazis would send a large group to the gas chambers. The gay man told her that a company was looking for weavers to work outside the camp. Tell them you can weave, he said. Lie.

“I was so young,” Kitty added. “He knew what was going to happen to me, I didn’t.” She did as she was told and survived, being liberated at the factory in May 1945. She went on to be a run a number of shops in Australia before moving to the Kings Cross neighborhood of Sydney where she witnessed the terrible toll HIV/Aids was having on the gay community there. She spent the rest of her life offering emotional and psychological support to those suffering from the conditions. She died in 2001.

Nothing more is known about her saviour.

Karl Gorath was 26 when he arrived at Auschwitz. He’d been denounced by a jealous former lover and arrested under the Nazis’ Paragraph 175 which outlawed homosexual acts – including kissing and hugging – and remained in force in parts of Germany until 1969.

was 26 when he arrived at Auschwitz. He’d been denounced by a jealous former lover and arrested under the Nazis’ Paragraph 175 which outlawed homosexual acts – including kissing and hugging – and remained in force in parts of Germany until 1969.

He was sent to the concentration camp at Neuengamme, near Hamburg. He had been training to become a nurse so was put to work in a prison hospital at a subcamp. But having refused to reduce food rations to Polish inmates, he was punished by being transported to Auschwitz. Given that his crime was now seen as political, he was forced to wear a red triangle and tattooed with the number 124630.

He worked in the sickbay of Auschwitz I until nine days before the camp was liberated when he was transported in freezing cold weather in an open freight car to Mauthausen, near Linz in what was Upper Austria. The journey took 11 days.

He was moved again as Allied armies closed in on Nazi Germany and was finally liberated by the Americans on 6 May 1945.

In his memoirs, he claimed that two younger Poles, Tadeusz and Zbigniew, became his lovers in the camp. Incredibly, he goes on to say: “I had my own room as a block supervisor this is where I spent the happiest days of my life, with Zbigniew.” He adds that only once in his life did he experience such deep love from another man, and that it was “here, in the camp, among all the misery surrounding us, never before, and never again—never more: I met the love of my life in Auschwitz.”

Tadeusz and Zbigniew both died in Auschwitz.

You would hope that Karl’s troubles ended after his liberation but that’s not the case. Gay holocaust survivors could be re-imprisoned for “repeat offences”, and were kept on lists of “sex offenders”. Under the Allied Military Government of Germany, some homosexuals were forced to serve out their full terms of imprisonment, regardless of the time spent in concentration camps.

Karl was re-arrested in March 1946, sent for trial and sentenced to five years in jail. All appeals for a pardon and clemency were turned down and he wasn’t released until April 1951. As other groups seen as undesirable by the Nazis successfully pursued claims of compensation for their suffering, Karl’s efforts were thwarted on the grounds that he had a “criminal record” and that he had not been persecuted because of his race or belief.

As recently as May 1975, Karl, then aged 62, was denied a pension because “the period between 1/8/39 to 8/5/45 cannot be recognized as substitute time” for work. In other words, being at Auschwitz wasn’t bad enough!

As recently as May 1975, Karl, then aged 62, was denied a pension because “the period between 1/8/39 to 8/5/45 cannot be recognized as substitute time” for work. In other words, being at Auschwitz wasn’t bad enough!

Appeals against this ruling were all finally dismissed in February 1980. Karl Gorath died in March 2003 at the age of 90. Paragraph 175 was not removed from the statute books in full until 1994.

Ernst Ellson was born in 1904. He was Jewish but arrested in November 1940 after a male prostitute told the police that he was a client. Ernst was jailed for four months after being found guilty of “perverted promiscuity.” He had been under surveillance since 1935.

On the day he was released from prison, the Gestapo were waiting for him with an arrest warrant. It stated: “It is to be feared that, if left at large, he will persist in behavior that is harmful to the national health.” The document was signed by one of the architects of the Final Solution, and the head of the security service, Reinhard Heydrich.

Ernst was sent first to Buchenwald, near Weimar in Germany, where some 56,000 people were to die, then Gross Rosen, which is now part of Poland, where some 40,000 inmates lost their lives. He was deported to Auschwitz on 16 October 1942.

He had lived for 18 months in the first two camps but survived just five weeks in the horrors of Auschwitz.

Manfred Lewin was gay and Jewish. He lived in Berlin and was ordered to be deported in 1942 along with his parents.

His boyfriend, 19-year-old Gad Beck, got hold of a Hitler Youth uniform and tricked the guards at the detention center into releasing Manfred, who he said was needed for slave labor. They walked out of the gates together, but Manfred decided he couldn’t leave his family behind and turned back. He was shipped to Auschwitz where he died, aged just 22.

Gad survived the war and in an interview in 2000, 12 years before his death, recalled the loss of his “great, great love.”

Gad survived the war and in an interview in 2000, 12 years before his death, recalled the loss of his “great, great love.”

Hermann Bartel was a decorator. He was gay. Sent to Auschwitz on 6 December 1941, he died there on 2 March 1942, aged 41. Erwin Schimitzek was a gay commercial clerk. He was sent to Auschwitz on 22 August 1941. He died there in January the following year. He was 23. Agricultural worker Emil Drews arrived at the death camp the same day and died a few days before Erwin. He was 58.

Hermann Bartel was a decorator. He was gay. Sent to Auschwitz on 6 December 1941, he died there on 2 March 1942, aged 41. Erwin Schimitzek was a gay commercial clerk. He was sent to Auschwitz on 22 August 1941. He died there in January the following year. He was 23. Agricultural worker Emil Drews arrived at the death camp the same day and died a few days before Erwin. He was 58.

Gay shopkeeper Max Gergia spent three months at Auschwitz before dying. He was 37. Emil Sliwiok suffered the same fate, he was 28. Waiter August Pfeiffer was deported to Auschwitz, arriving there on 1 November 1941. Aged 46, he died at the end of December. Walter Peters, a doctor, died five days after arriving at the camp. He had just turned 51. Willi Pohl was 35 when he died. He was a textile worker and a gay man. Rudolf von Mayer was a judge. He was gay. He arrived at Auschwitz on 30 May 1941 and died three months later, just days before his 37th birthday. Willi Kacker was 36 when he died. Farmer Oskar Birke was 48. Otto Hertzfeld, 35; butcher Johann Majschek, 53; gardener Franz Ruffert, 39; office assistant Richard Schiller, 41; tailor Josef Klose, 47; electrician Hugo Prabitzer, 40.

All gay. All sent to Auschwitz. All died.

And there were more – not to mention the countless numbers whose exact fate remains unknown either at the camp or after being transported elsewhere before the end of the war. Gay men; killed simply because they loved another man.

If you take one thing from all this, this Holocaust Memorial Day, maybe it should be that the Nazis didn’t just kill individuals. As historians have pointed out, one of the gay men who died might have gone on to invent something incredible, they might have become a great diplomat or leader who avoided another murderous war, the younger ones might have gone on to become scientists or doctors, who found a cure for cancer, dementia, ebola, heart disease, or HIV. The common cold – who knows?

The Nazis didn’t just kill individuals: they killed the future.