Leonard Bernstein was highly influential in American cultural life. As the composer of musicals, operas, ballets, and film scores including West Side Story, Candide, On the Town, he lived at the center of popular culture. He was also bisexual, horny, studly, and married with children but engaged with male lovers in a way that was very out for his time. Bernstein – white, wealthy, talented, and surrounded by protective admirers – was also enormously privileged. No doubt that privilege allowed him to skate through the dangerous maze of being gay or bisexual at a time when many men suffered tremendously. He lived the way he wanted – at the center of a world of his own making.

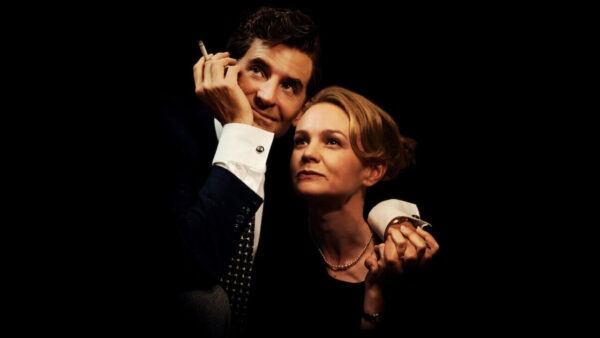

Maestro, the new film by Bradley Cooper, delves into a specific period of Bernstein’s life when he was married to an understanding woman who supported him for many decades. It was, as one can imagine, a difficult marriage filled with a great deal of compromise.

Cooper does quadruple duties on Maestro – starring, writing (with Josh Singer), directing, and producing. There’s also a little dancing. It’s revealing of Cooper’s depth of imagination and also his enormous ambition as an artist and storyteller. Surprising and unpredictable, the film will stick with you long after it has ended. Cooper is pushing his way into the upper echelon of contemporary filmmakers with himself in the center in a go-for-broke performance that dazzles.

Cooper does quadruple duties on Maestro – starring, writing (with Josh Singer), directing, and producing. There’s also a little dancing. It’s revealing of Cooper’s depth of imagination and also his enormous ambition as an artist and storyteller. Surprising and unpredictable, the film will stick with you long after it has ended. Cooper is pushing his way into the upper echelon of contemporary filmmakers with himself in the center in a go-for-broke performance that dazzles.

A Bernstein quote opens the film. “A work of art does not answer questions, it provokes them; and its essential meaning is in the tension between the contradictory answers.” Likewise, Maestro does not answer definitively how Bernstein was able to juggle the different facets of his personality but does take us into those moments of tension. As an actor, Cooper disappears completely into the character of Leonard Bernstein. The conducting scenes alone demonstrate a previously untapped level of commitment in Cooper’s screen performances. It is the best performance by a male actor I’ve seen this year.

There are many Oscar-worthy moments here, so it is surprising that it seems to be poised to lose those awards to the slogfest that is Oppenheimer, a movie that would have bombed at its opening had it not been cleverly marketed with Barbie. But alas, Oppenheimer seems destined to take it all this year so Cooper will have to be satisfied with a copious number of nominations.

Don’t spend even a moment feeling sorry for him. Instead, recall with a twinge of bitterness that 30 years ago Barbara Streisand’s equivalent work on Yentl was resoundingly snubbed of major nominations let alone actual trophies. Perhaps as in Streisand’s case, the voting members of the Academy feel that Cooper is already too successful. They do love an underdog.

Carey Mulligan as Bernstein’s wife Felicia is exceptional. Her acceptance of his desire for men is dealt with almost blithely but clearly. Felicia chooses a marriage with complications to have Bernstein in her life. She sacrifices her own career as a promising actress to be a wife, mother, and partner to Bernstein. She’s just the most gifted actress. Mulligan artfully projects Felicia’s internal conflicts without words in several pivotal moments where Felicia finds herself being pushed to the edges of Bernstein’s spotlight. It’s a career high for her as an actress and it will be a difficult role to top, although it will be delightful to see it happen.

as Bernstein’s wife Felicia is exceptional. Her acceptance of his desire for men is dealt with almost blithely but clearly. Felicia chooses a marriage with complications to have Bernstein in her life. She sacrifices her own career as a promising actress to be a wife, mother, and partner to Bernstein. She’s just the most gifted actress. Mulligan artfully projects Felicia’s internal conflicts without words in several pivotal moments where Felicia finds herself being pushed to the edges of Bernstein’s spotlight. It’s a career high for her as an actress and it will be a difficult role to top, although it will be delightful to see it happen.

There’s an early moment in their courtship where Cooper creates a surrealist scene where Leonard and Felicia are both watching and participating in a ballet sequence out of On the Town. It suggests how Leonard explained his approach to bisexuality and how Felicia might have come to understand and accept it. It’s a wordless musical sequence that stirs up emotions in all the best ways and exemplifies the daring and ambition in Cooper’s filmmaking. Cooper is not afraid to place himself in vulnerable positions as an actor. It would be hard not to admire someone willing to take big, risky swings at greatness.

On the whole, Cooper is generous to his cast. In all the supporting roles, even small ones, Cooper lets everyone shine. For characters like Matt Boomer’s clarinetist and one of Leonard’s lovers, and Sarah Silverman as Leonard’s sister Nina Bernstein, Cooper gives them the kind of long close-ups that allow them to relay the subtext of the moment. It’s the stuff of the actor’s dreams, and the actors reward his largesse with exceptional commitment.

On the whole, Cooper is generous to his cast. In all the supporting roles, even small ones, Cooper lets everyone shine. For characters like Matt Boomer’s clarinetist and one of Leonard’s lovers, and Sarah Silverman as Leonard’s sister Nina Bernstein, Cooper gives them the kind of long close-ups that allow them to relay the subtext of the moment. It’s the stuff of the actor’s dreams, and the actors reward his largesse with exceptional commitment.

Cinematography, lighting, and editing meld together seamlessly. Moment to moment the look and feel of the film mirrors the film-making techniques of the time the story is set. It’s noir-ish in the 1940’s and garish in the style of early video in the scenes set in the 70’s. Mathew Libatique, who did the same duty on Cooper’s A Star Is Born, is the Cinematographer. The film is frequently gorgeous. There are visual delights at every turn. Cooper frequently backlights his characters, leaves shadows over their faces, or keeps the camera at a distance to beguiling, sometimes uncomfortable effect.

Expert editing on view here is credited to Michelle Tesoro, who deftly handles the film’s shifts between fantasy and the starkest reality. Every technical element from sets to sound is state of the art. At the same time, there is so much expert craftsmanship in this film that at times it can pull focus from the story as you admire the skills on display. There’s just the tiniest feeling of watching a gifted film student’s attempt to cram every auteur’s trick onto the screen.

The make-up work here is also truly superb. It’s certainly a new high watermark in the art of prosthetics credited to Vivian Baker. Much has been made of Cooper’s prosthetic nose and whether it was necessary but there’s no denying that it’s completely believable. When we see Bernstein as an elder statesman playing the piano and reminiscing for a camera crew, the aging makeup is thoroughly convincing.

More concerning to the LGBT+ audiences is whether this film treats the subject of bisexuality in a way that is meaningful to that community. The short answer is that it does, but it may not quell the discomfort of some to see one of the biggest LGBT+ heroes in a biopic under the control of a cis-gendered and straight actor, writer, and director. Only time and distance from the politics of the moment will tell if Maestro succeeds as a historic document. But as a popular entertainment, it does succeed, like most of Bernstein’s artistic output, tremendously well.

Guest Contributor: James Judd is a freelance writer, a performer, a frequent contributor to NPR, and a Creativity Coach. He lives on Cape Cod.