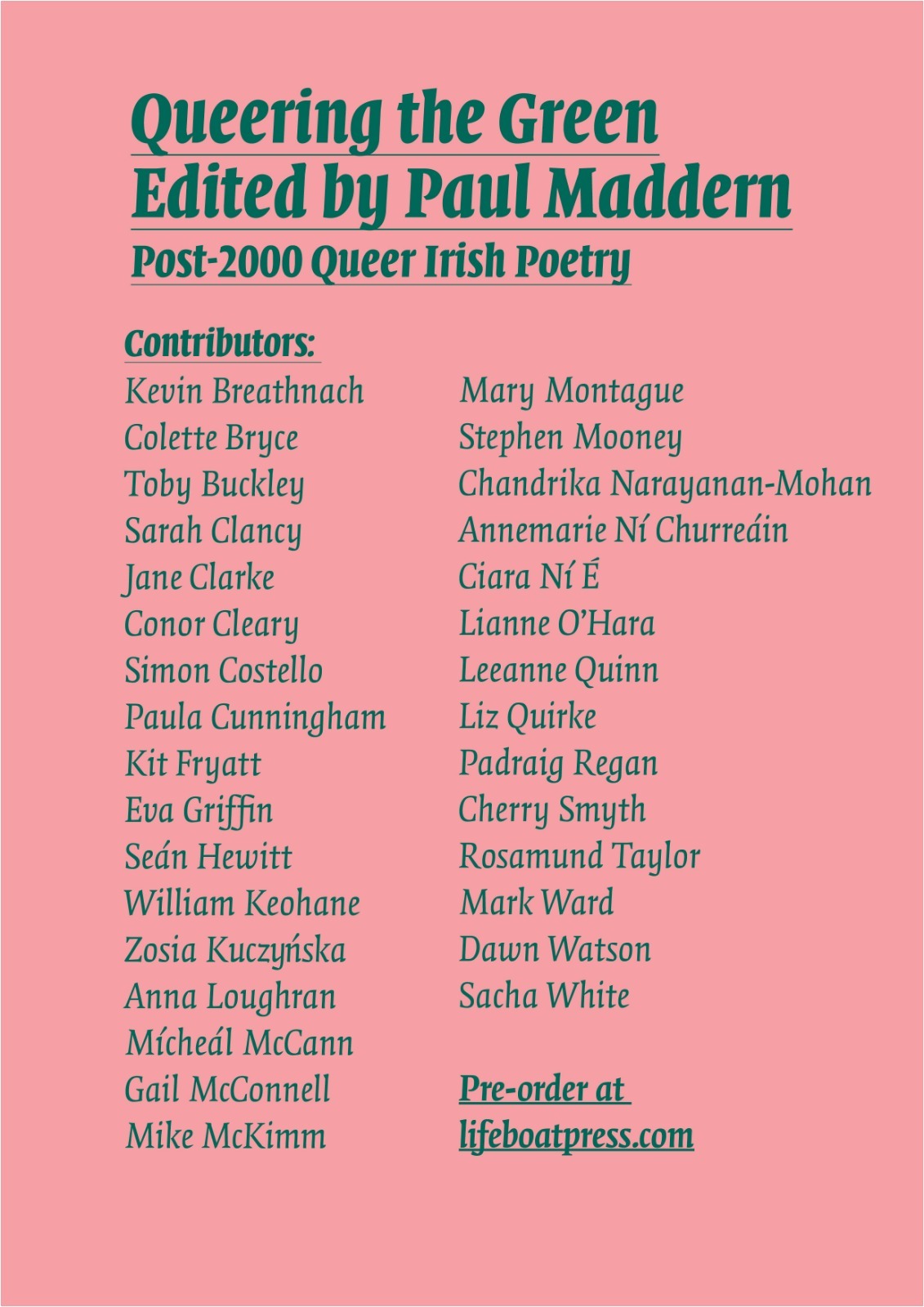

I have waited a long time to get my hands on this book: my own copy took a while to arrive with me, but – more importantly – the anthology itself feels long overdue; it’s about time somebody undertook the difficult, necessary work of editing a collection of contemporary queer Irish poetry. After making my emotional journey through these pages, I am so glad that The Lifeboat Press accepted this challenge. Queering the Green is a thoughtful and important work indeed.

I have waited a long time to get my hands on this book: my own copy took a while to arrive with me, but – more importantly – the anthology itself feels long overdue; it’s about time somebody undertook the difficult, necessary work of editing a collection of contemporary queer Irish poetry. After making my emotional journey through these pages, I am so glad that The Lifeboat Press accepted this challenge. Queering the Green is a thoughtful and important work indeed.

The anthology is generous in extent and in scope; it features established and emerging poets alike, from both the north and the south of Ireland. While these poets take vastly different approaches to theme, structure, and form, they are united by a keenly sensitised queer subjectivity; a queerness that shapes and drives their engagement with language, history, and national identity.

In recent years notions of the queer have proliferated and flourished; as editor, Paul Maddern points out in his introduction, we can think of ‘every poem’ as ‘a queering of the language’, yet ‘only we are queer’ (xxii). This makes sense to me. The queer happens inside of language, but language is not magically separable from the bodies and communities that make and use it. The prevalence and rising status of the queer within discourse comes with the real risk of erasing those bodies and communities. Queerness is not rhetorical or abstract; it is fiercely, often perilously, embodied. Queerness is situated. Queerness is lived. One of the things that makes Queering the Green such an exciting and significant book is that it reinstates vulnerable queer bodies at the centre of queer poetics.

In Padraig Regan’s ‘Salt Island’, which serves as a poetic introduction to the collection, the queer speaking subject is centred in – and interrupts – the rural Irish landscape. Regan’s speaker describes themselves as: ‘the little rip in the surface/ where my eye might snag’, clashing with and obtruding into the natural scene in his ‘red tartan’. I adore this poem, for the way it reclaims and conjures a queer pastoral, but also for the way it disrupts the long-naturalised image of the rural gaeltachtaí as the repository of some kind of essential Irishness, defined in terms of the traditional, the normative, the pure. ‘Salt Island’ is a work of nature writing par excellence; it is also a subtle refusal of the way national belonging is made and policed. For all and any of us who have felt the pain of loving a country that did not quite love us back, this poem resonates powerfully.

In Ireland, and for those of us with Irish heritage, language and land are explicitly and often painfully entwined. During an Drochshaol, the places where spoken Irish thrived were hardest hit. Famine delt damage to territory and to tongue. As communities died or were driven into exile, a common language scattered. Historically, occupying authorities in Ireland have found it expedient to prohibit and punish the use of the Irish language. Still vivid in my own memory are discussions around the ban on speaking Gaelic in Long Kesh because Irish itself was deemed ‘sectarian’, bearing with it a collective and threatening insurrectionary pressure. I grew up understanding spoken Irish as political, rebarbative, inextricably tied to suffering, to protest, and to a (usually masculine) normative performance of identity. For this reason, especially Ciara Ní É’s Irish language poems of wistful intimacy feel profound. These poems focus on tactile and sensory pleasure, on a generous, though sometimes melancholy, extension of affection towards an other other. These poems perform an act of queer recuperation, they invite us to image an Irish of small things; of little-huge connections, as in ‘Leabhardhamhsa/Bookdance’ (p.274) where owners of a book, decades apart, become ‘name-neighbours’ across gulfs of time. The act of naming, so often misused, so often divisive, forms the basis of a supernatural communion between the living and dead.

Elsewhere, as in Kevin Breathnach’s ‘Morphing’ poems (pp.6-10) words infiltrate and warp the structural integrity of bodies, and language – specifically English – is not merely subject to but an instrument of queering. Breathnach’s poems give us ‘morphing babble in a field of swept/ horror rhymes for muted words’ (p.6), ‘the yell of brief intentions’ and the ‘dreary/ attic drone’ (p.7); they conjure ‘life as reckless heated words’ (p.8) and ‘the smack of a plague racket stream’ (p.9). ‘shit on the grammar’ writes Breathnach in ‘Morphing #2’ (p.6) at once exposing and refusing the violence contained within hegemonic English, subverting the sanctioned syntaxes of lyric to strange, queer ends.

Throughout the anthology, the intersection of language and body is evoked in a variety of provocative ways, but for me one of the most arresting pieces is Mark Ward’s ‘The Swamp’ (p.368), written after the painting La Palude by the contemporary Italian painter Roberto Ferri. Ferri’s work is heavily influenced by the Baroque, and La Palude is a remarkable painting, reminiscent of Caravaggio. It features a single hunched figure in a dark, obscure space, his back toward the viewer. The figure’s dipped head is in shadow, his face averted. Cowed and twisted, in obvious pain, his body bears the marks of violence. Ward describes this figure in visceral detail, his ‘backbone, a reptilian wound’. This picture of Ferri’s hunched and suffering form is haunting; it conjures an image of deformity, of absolute abjection, where the reader feels in equal parts disgust and pity. But, in the final stanza, the poem catches us off guard by drawing our attention to a tiny detail in Ferri’s painting, a detail we may have so easily missed: a ‘fin growing/ alien from the foot, an almost toe,/ pointless, primordial.’ (p.369). The view tilts on its axis, and we are reading a poem or looking at a picture, eloquent of queer shame; a poem that speaks to queer visibility and queer vulnerability, especially in Ireland.

Historically, to be queer has been to be visible in all of the wrong ways: a target for ridicule and violence; a medical curiosity and a sideshow spectacle, a sinner, a sin. To be queer was to be a cautionary tale, a dirty secret, and an ugly rumour. Your visibility was punitive and policed. You were supremely, dangerously visible, but rarely ever seen, and never heard. You were whispered into euphemism, you were papered over, painted out, redacted, censored, enclosed in a dark space, voiceless. The only proof that you existed at all was the hostile regard to the crowd. This contradiction seems to be the heart of Ferri’s painting and of Ward’s poem. In describing the scene as ‘primordial,/ some Beckett set design’ Ward seems to signal a specifically Irish context for the ‘swamp’. By using ‘primordial’ in both his opening and closing stanzas, Ward draws an explicit link between place and the suffering felt by the bodies that inhabit that place. The ‘swamp’ is not literal, it is simultaneously a figure for the seething morass of historical bigotry and persecution and the mental anguish of the silenced queer subject who cannot but experience themselves as freakish or monstrous.

Historically, to be queer has been to be visible in all of the wrong ways: a target for ridicule and violence; a medical curiosity and a sideshow spectacle, a sinner, a sin. To be queer was to be a cautionary tale, a dirty secret, and an ugly rumour. Your visibility was punitive and policed. You were supremely, dangerously visible, but rarely ever seen, and never heard. You were whispered into euphemism, you were papered over, painted out, redacted, censored, enclosed in a dark space, voiceless. The only proof that you existed at all was the hostile regard to the crowd. This contradiction seems to be the heart of Ferri’s painting and of Ward’s poem. In describing the scene as ‘primordial,/ some Beckett set design’ Ward seems to signal a specifically Irish context for the ‘swamp’. By using ‘primordial’ in both his opening and closing stanzas, Ward draws an explicit link between place and the suffering felt by the bodies that inhabit that place. The ‘swamp’ is not literal, it is simultaneously a figure for the seething morass of historical bigotry and persecution and the mental anguish of the silenced queer subject who cannot but experience themselves as freakish or monstrous.

It is no coincidence that monsters, chimeras, and witch-women appear across the anthology. In Rosamund Taylor’s exquisite and chillingly realised ‘The Names We Called You Meant Nothing to Me’, supressed desire expresses itself in a fever of socially-sanctioned persecution, and a woman deemed a ‘witch’ is hanged, or hangs herself (p.348). This final ambiguity is a deeply unsettling element of the text, which Taylor exploits to great effect, leaving the reader to sit in their discomfort, newly sensitised to the consequences of words and how we use them. While the poem unfolds against a backdrop of historical witch hysteria, the story is still miserably relevant, and particularly sharp for any woman who has found herself on the receiving end of homophobic abuse. Witch hunts historically blurred homophobia and misogyny. There’s a passage in the Malleus Maleficarum – a 15th century witch-finder’s handbook – that genuinely describes witch-women who steel men’s penises and ‘put them together in a birds’ nest or shut them up in a box, where they move about like living members, eating oats or other feed’. It would be hilarious if real women had not died as the result of such beliefs. This absurd story renders literal the emasculation men fear from queer women. Women who do not need men, whose sexuality is not framed in reference to male desire have often been characterised as unnatural and malevolent. The true horror of Taylor’s poem is that fear of being thought unnatural and malevolent leads to a fatal betrayal of self and other.

Elsewhere, Taylor’s magical other is not abject but gloriously resistive. In ‘When My Wife Is A Werewolf’ (p.350) Taylor uses the conceit of therianthropy – the magical transformation of humans into animals – as a figure for the power of queer desire to remake futures, selves and lives. It is a survivalist hymn of solidarity and one of my favourite poems in the collection. In the final stanza Taylor’s speaker is vulnerable, yet safe; able to risk vulnerability because she is cherished and protected: ‘I am small/ as a rabbit against her/ yet I feel huge/ as the forest she longs for’. I can’t think of a better queer victory than that.

And queer victory is coming. Slowly, but perceptibly. This feeling is palpable across the anthology, perhaps because of its focus on living queer poets writing over the last twenty-two years. The Irish queer as represented by Queering the Green feels urgent, emergent, porous, in the process of being made. This sense of excitement and hope is reflected in the Ireland beyond the text, which has experienced a seismic shift over the last couple of decades in how it sees, legislates, and talks about queer persons. Some of these changes are momentous milestones, political with a capital ‘P, others are smaller, more daily, but no less important: the appearance of An Queercal Comhrá, Dublin’s first Queer Irish language conversation group, and the publication of an Irish language Queer Dictionary, An Foclóir Aiteach, in 2018. Tiny steps in a larger struggle but indicative of much welcome change in the air.

That said, Queering the Green does not succumb to some kind of rose-tinted and reality adverse celebration of queerness, there is a sense of mourning and of reckoning that permeates this anthology. Ghosts haunt Queering the Green, the dead are a tangible presence, brushing up against the living in often unexpected ways. This finds its most vivid expression in Simon Costello’s poem ‘Aftermath of a Landslide’ (p.84), where the bones of the dead literally resurface. Costello’s poem confronts Ireland’s long continuities of violence in a way both direct and indirect. The speaker begins with a description of a YouTube video mocking an Irish participant on Love Island: ‘The American playing the Irish model/ said she came from the part of Ireland/ where the soil is made of bones// That was a good one’. A good one because couldn’t that be anywhere? From our peatbog ‘bronze age ancestors pulled up/ by the roots of their amber-dust hair’, to those who perished in the famine, to the disappeared victims of the IRA, Ireland is heavy with her dead, so much so that this long, sad history has been hollowed out of context, specificity and meaning. ‘Bones’ become an empty signifier, a metonym for Ireland and Irishness, a casual currency, mockingly evoked in an online video.

In the third stanza, Costello pivots from this disturbing description of numb affect to one of ‘the buried arrived at our doors’. No one was ‘surprised’. Throughout the poem the dead are repeatedly referenced through their online appearance and reception, recycled into trending content, into reposts, pinned tweets, videos, texts, screensavers. This relentless mediation manages to suggest both a populace – and a speaker – desensitised to death and one energetically avoiding the pain of it. Only in the final stanza is Costello’s speaker physically connected to the mud and muck of the landslide, ‘wading through the heaving churchyard’ to be ‘the first to sink my hands earthwards/ finding you/ like an undiscovered bomb’ (p.86). The ending wallops you. There’s an experience of loss there that cannot be rerouted, evaded, or ignored. I think Costello’s poem asks some uncomfortable questions about queer loss at the point where a personal experience of grief intersects broader histories of violent death. It frames a question I have often had cause to ask myself: how are we to meaningfully mourn when our experience of loss is not accommodated by any of the available nationalistic or religious scripts? If grief and the act of remembrance are experienced in and through physical spaces both public and private, then what should grief look like or mean for those of us with a vexed relationship to such spaces? Ireland folds her dead into a myth and iconography of loss from which many of us are excluded. In the end the speaker must thrust his hands into the earth, must recover and carry his loss for himself.

The Irish word for the odd or uncanny is aisteach. The Irish word for a queer person is aiteach. The poems in Queering the Green walk between these words and worlds; refracted through the lens of queer subjectivity, Ireland itself is made strange and new. There is a lot of sadness and struggle in this book, but there is also possibility, a chance to – as Sarah Clancy puts it in ‘A prayer to St Bridget in her most pagan incarnation’ – summon ‘a whole new language’ (p.49). Not just to name the damage done to us, but to articulate resistance; to mourn and celebrate ourselves and each other.

QUEERING THE GREEN: POST-2000 QUEER IRISH POETRY EDITED BY PAUL MADDERN https://lifeboatpress.com/queering-the-green

Review by Fran Lock

Dr Fran Lock is the author of numerous pamphlets and nine poetry collections, most recently Hyena! Jackal! Dog! (Pamenar Press, 2021)