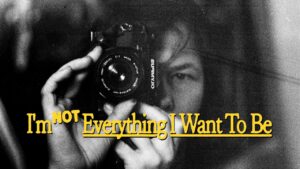

Making a film just from photos is no easy task, and takes a great risk of whether it will succeed. Like in the case of Czech writer/director Klára Tasovská, who opted to make a memoir of Czech photographer Libuše Jarcovjáková’s life and work through some 3000 prints. She may not be a household name to many (including ourselves), but in her world, her work has been compared to the great Nan Goldin, which is an extraordinary flattering compliment and one that made us curious enough to know more. It was, after all selected as the Czech entry for the Best International Feature Film at the 98th Academy Awards.

Most of the photos come from a 21-year period between 1968 and 1989, spanning momentous occasions in history and the artist’s own life. In the latter, she is very hard on herself, continually searching for who she really is, and documenting every single moment of that journey with her camera. She became an adult at the moment the USSR took over Prague, and her desire to attend college was held back by her parents’ bourgeois background. Instead, she was ordered to work at a printing press, where she managed to have some illicit sex when she was still on duty. She then had to appeal to the state to get an abortion, but the second time she needed one, she had to resort to a backstreet operator. Somewhere alomg he way she got involved in a long, unhappy marriage.

An acquaintance got her a trip to Japan in 1979 , which offered a glimpse of a freer world, and the possibility of her photography being taken serious but she wasn’t able to remain in the country. She was in Berlin when the wall came but also around that time, she immersed herself in ‘80s Czechoslovak queer culture, before the decriminalization of homosexuality in the country. She became a regular at the gay bar T-Club, which contributed to some of her happiest moments, plus the club itself and the people she met there inspired some of her best work. Yet Jarcovjáková’s documentation of the club also had the potential to become a form of surveillance. So after some violence there, she turned over some of her photos to the police, only later realizing how dangerous this could be. She stopped shooting in the club.

An acquaintance got her a trip to Japan in 1979 , which offered a glimpse of a freer world, and the possibility of her photography being taken serious but she wasn’t able to remain in the country. She was in Berlin when the wall came but also around that time, she immersed herself in ‘80s Czechoslovak queer culture, before the decriminalization of homosexuality in the country. She became a regular at the gay bar T-Club, which contributed to some of her happiest moments, plus the club itself and the people she met there inspired some of her best work. Yet Jarcovjáková’s documentation of the club also had the potential to become a form of surveillance. So after some violence there, she turned over some of her photos to the police, only later realizing how dangerous this could be. She stopped shooting in the club.

Throughout the film, her work at times is deliberately blurred with slurred images, which requires a level of patience, yet on other occasions it is full of sharp, crisp images, which gives the film a disturbing edge but also cranks up the intrigue and our fascination with her story.

The film is a great introduction into the world of a very talented artist, who may now get the full recognition she deserves, and the fact that she is its narrator too, makes it all that much better