IN THE NIGHTMARE HOUSE

IN THE DREAM HOUSE is a mind-blowingly original book; not just because of its dreamy prose that weaves gothic aesthetics with hyperrealism, but also the incredibly sensitive subject matter – domestic abuse within a lesbian relationship. Sensitive for all the nuanced and well-argued reasons mentioned in the book, including the fear of failing on behalf of all queers by admitting that queer, or in this case, specifically lesbian relationships, can be as horrendously abusive as heterosexual ones. There is – understandably – the shame and fear of articulating this simple fact. It wasn’t until long ago when same-sex relationships were criminal and illegal in the US, and even today this is still the case in many countries. Therefore, when one is in a same-sex relationship, one’s body is inevitably politicized and the personal becomes very much political. It’s perfectly understandable why many queer people feel ambivalent about discussing abuse within homosexual contexts.

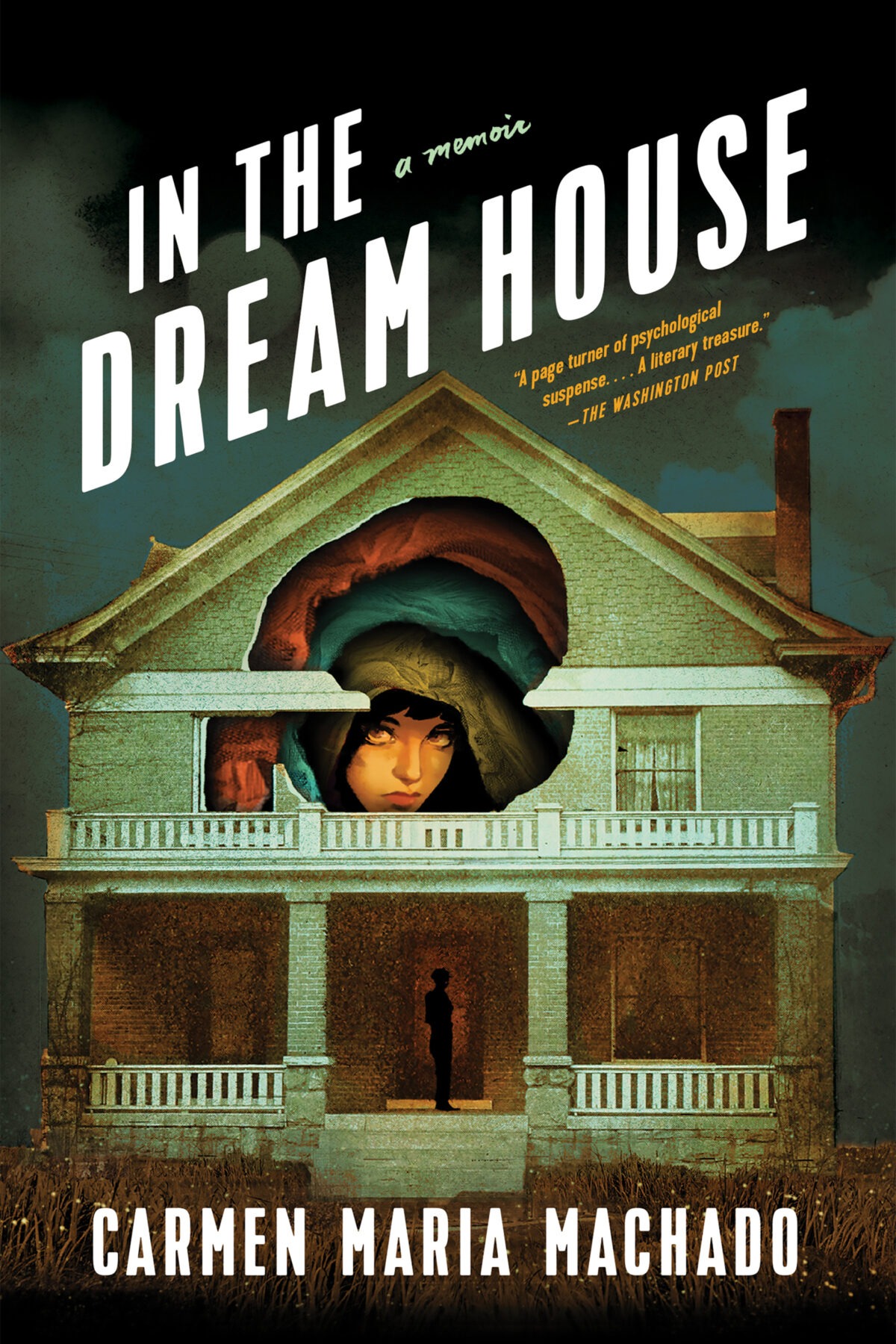

IN THE DREAM HOUSE is a mind-blowingly original book; not just because of its dreamy prose that weaves gothic aesthetics with hyperrealism, but also the incredibly sensitive subject matter – domestic abuse within a lesbian relationship. Sensitive for all the nuanced and well-argued reasons mentioned in the book, including the fear of failing on behalf of all queers by admitting that queer, or in this case, specifically lesbian relationships, can be as horrendously abusive as heterosexual ones. There is – understandably – the shame and fear of articulating this simple fact. It wasn’t until long ago when same-sex relationships were criminal and illegal in the US, and even today this is still the case in many countries. Therefore, when one is in a same-sex relationship, one’s body is inevitably politicized and the personal becomes very much political. It’s perfectly understandable why many queer people feel ambivalent about discussing abuse within homosexual contexts.

This innovative memoir is comprised of many small sections, each with a heading featuring Dream House, which is a euphemism for the cabin of Machado’s abusive lover in Bloomington, USA. The nameless ‘petite’ ‘blonde’ Harvard graduate charms Machado into a monogamous relationship, then gradually reveals herself to be a full-blown psychopath. She threatens Machado, she assaults her physically and psychologically, screams in her ears when she is jealous that Machado fancies everyone, including her own father, and then cheats on Machado and even then, doesn’t want to let her go.

But this book is more than just a linear account of being abused – it’s well-researched and well-argued – acknowledging why it is important for queer people, especially queer women, not to be romanticized and idealized. As women, we also already know, this romanticization and mythologizing often come with the price of erasure and being stripped of our humanity. Newsflash, (queer) women are also humans, and humanity has a ‘fundamentally problematic nature’ according to Machado. ‘Humanity’ is about ‘All the unique and terrible ways in which people can, and do, fail.’ Machado also argues that in a more equal world where queerness is ‘normal and accepted’, we can see that queerness is not about ‘entering paradise’, but it is about ‘the claiming of your own body: imperfect, but yours.’ There is also an intriguing section on ‘Queer Villainy’ where Machado directly addresses the importance of representations of ‘the queer villain’ through analyzing Stranger by the Lake:

We deserve to have our wrongdoing represented as much as our heroism because when we refuse wrongdoing as a possibility for a group of people, we refuse their humanity.

Machado defends the idea that queer does not ‘equal good or pure or right.’ This essential section ends with, ‘Let them have agency, and then let them go.’

In recounting the intense events of her life, Machado often uses the second pronoun ‘you’, rather than the more direct and common ‘I’. This unconventional choice of point of view disturbs the reader, even more, when she is narrating her trauma, as you are directly placed in the position of the narrator. If the reader has had their own trauma in regard to their queerness, which I have had, this effect is sometimes unbearable. It is too disarming, and yet too hypnotic and cathartic to avoid:

On that night, the gun is set upon the mantlepiece. The metaphorical gun, of course. If there were a literal gun, you’d probably be dead.

And because, in part, it is a decadently sensual read, in recounting the charming beginning of what later becomes an abusive relationship, Machado does a mesmerising job conveying the pleasures of being consumed by fulfilling one’s desire. Here’s an example of a sex scene from the beginning of the book, in which Machado has used the second person pronoun to convey the intensity of sex and desire in the relationship that ends up being abusive:

She kisses your top lip, then the lower one, like each one deserves its own tender attention. She leans away and looks at you with the kind of slow, reverent consideration you’d give to a painting. She strokes the soft inside of your wrist. You feel your heart beating somewhere far away, as if it’s behind glass.

‘I can’t believe that you’ve chosen me,’ she says.

In the room, she takes off your new underwear and buries her face between your thighs.

Whilst in the Dream House, soon enough, the reader realizes they are in fact in the Nightmare House. However, Machado, through her artful prose, meticulous research, and knowledge of lesbian history, makes this an undoubtedly memorable and necessary stay for the reader.

In the Dream House A Memoir Carmen Maria Machado https://www.graywolfpress.org

Carmen Maria Machado is an American short story author, essayist, and critic frequently published in The New Yorker, Granta, Lightspeed Magazine, and other publications. She has been a finalist for the National Book Award and the Nebula Award for Best Novelette

Review by Golnoosh Nour.

Golnoosh Nour is the author of The Ministry of Guidance and Other Stories. Her poetry collection Rocksong will be published in October 2021 by Verve Poetry Press. Her work has also been published in Granta, Columbia Journal, and Poetry Anthology amongst others. Golnoosh has performed her work across the UK and internationally. She teaches Creative Writing at the University of Reading. She’s the co-editor of Magma 80 and the anthology Queer Life, Queer Love forthcoming with Muswell Press.