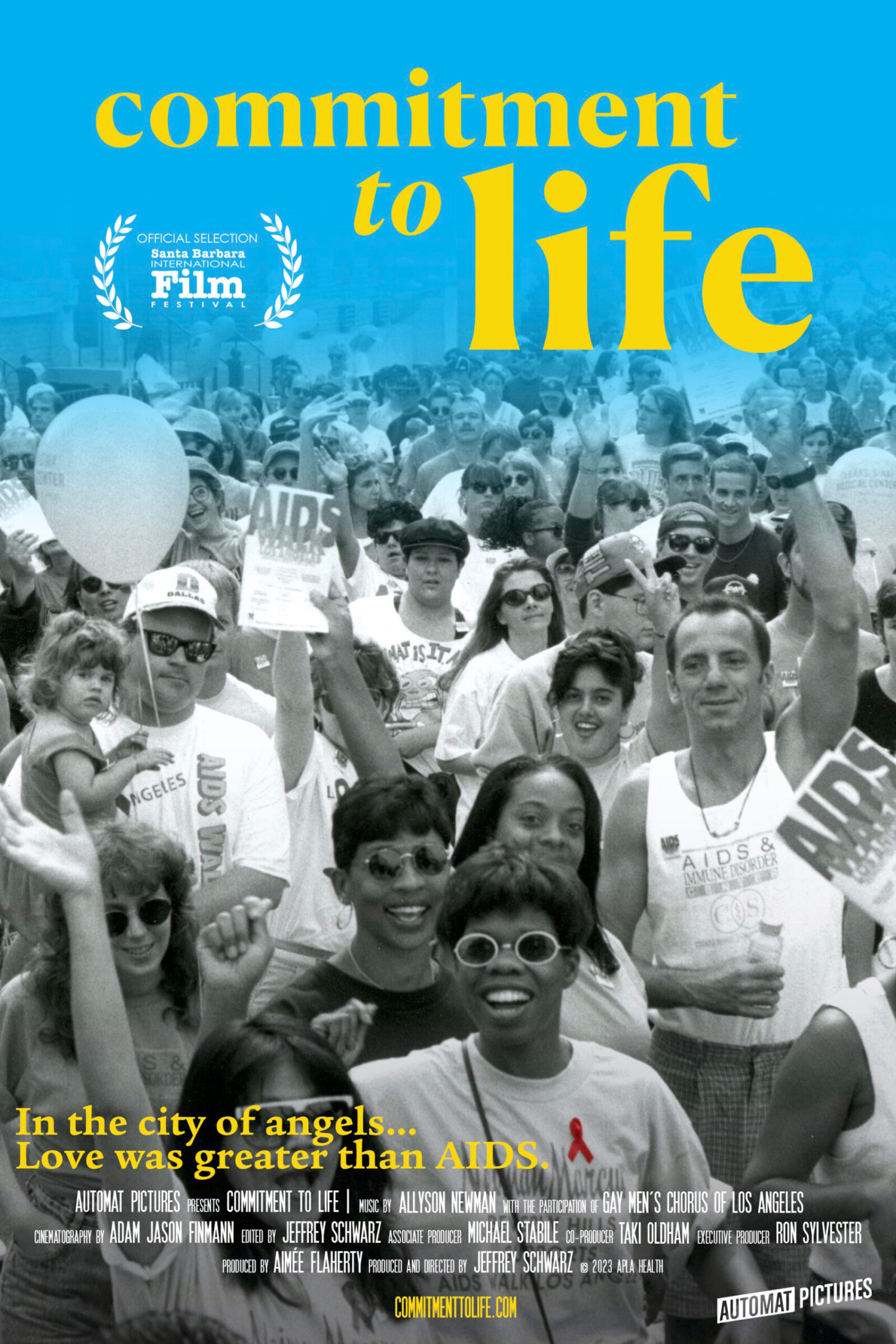

Los Angeles, 1981. The dark shadow of the global HIV/AIDS epidemic was just beginning and, for the time being, the thriving queer community members of West Hollywood’s ‘BoysTown’ were living life to the full, blissfully unaware of what lay ahead for them. Emmy Award-Winner film-maker Jeffrey Schwarz begins his latest documentary here and takes us on the subsequent 40-year-plus journey of the HIV/AIDS disease and how it affected the people of Los Angeles, and how the community came together to treat the sick, raise awareness, fight White House apathy and educate each other on safe sex.

Los Angeles, 1981. The dark shadow of the global HIV/AIDS epidemic was just beginning and, for the time being, the thriving queer community members of West Hollywood’s ‘BoysTown’ were living life to the full, blissfully unaware of what lay ahead for them. Emmy Award-Winner film-maker Jeffrey Schwarz begins his latest documentary here and takes us on the subsequent 40-year-plus journey of the HIV/AIDS disease and how it affected the people of Los Angeles, and how the community came together to treat the sick, raise awareness, fight White House apathy and educate each other on safe sex.

It’s easy to forget how much fear and confusion was caused by the onset of the disease back in the early 1980s. For the first few years, there was no way to test to see if you had the HIV virus and there was also no treatment available other than managing some of the symptoms. The method of transmission was also unknown meaning that patients were often refused treatment by fearful medical staff – including mortuaries. Family members often disowned them and people with HIV often lost their jobs and insurance benefits. The shell-shocked community of West Hollywood quickly realized that Ronald Reagan’s Republican Government had no interest in dealing with HIV/AIDS, and that, if anything was going to happen, they needed to do it themselves. This led to the formation of one of the first AIDS charities – AIDS Prevention Los Angeles (APLA).

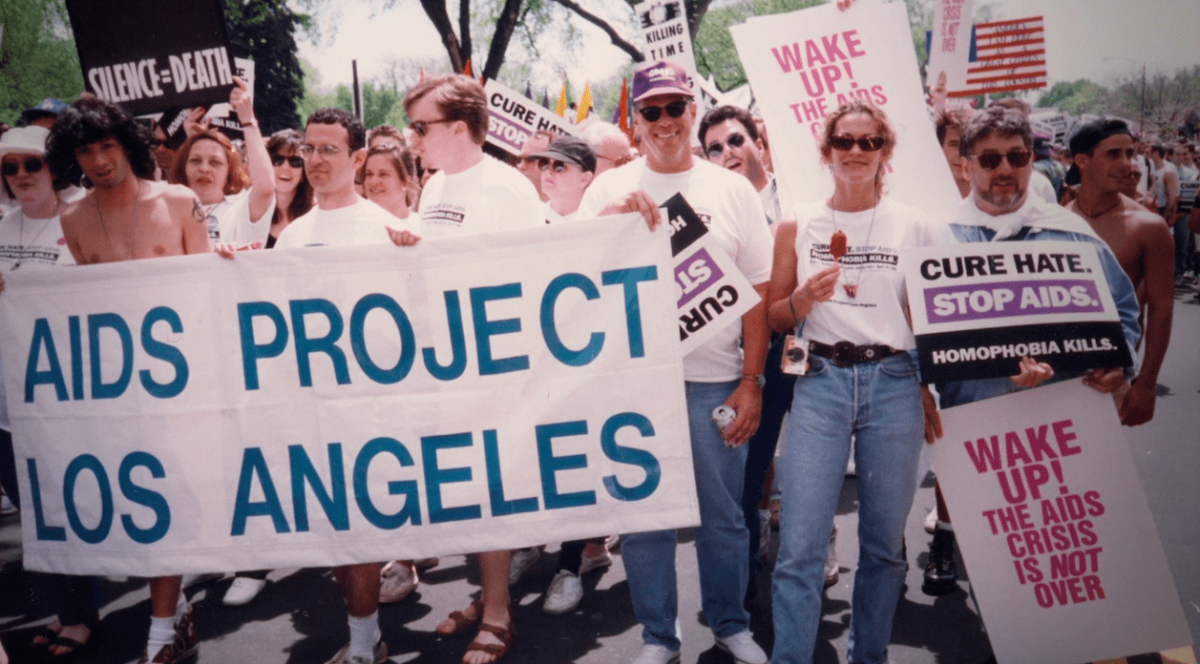

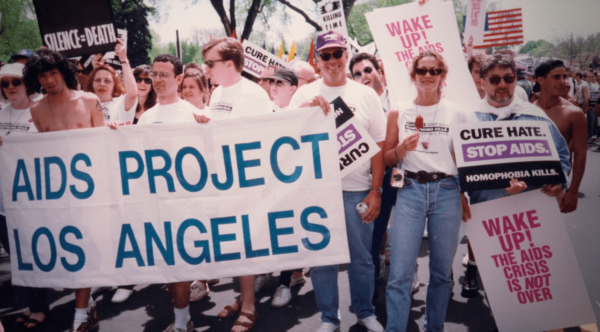

Formed in 1982 when nationally there were approximately 450 cases of AIDS, APLA set up an AIDS hotline to inform worried members of the community. They reached out locally to combat ignorance, fear, and bigotry and set up the ‘Necessities of Life’ program to care for people too sick and poor to feed themselves and to provide ‘Buddies’ for those battling the disease alone. Remember that at this time many queer people lived very closeted lives with few close friends. Many of the APLA staff members were HIV positive and a third of them died in its first year of existence alone. Over the next couple of years, it became clear that the disease was blood-borne and largely spread by sexual contact or by sharing syringes. Gay men, however, were initially very reluctant to change their behavior – behavior that had been repressed for many years in the small US hometowns they had escaped from, and so spreading the safe sex message became a crucial part of APLA’s work.

By 1985 there were 16,000 cases of AIDS nationally and yet the government had still not mentioned the word AIDS. 25% of the cases in the US were in California and most of those concentrated in the Los Angeles and San Francisco areas. The Hollywood film studios, with their high percentage of queer employees, were particularly badly affected. APLA needed ever-increasing funds to deal with the avalanche of people requiring its support. The idea of a ‘Commitment to Life’ fundraising dinner was pitched to the movie industry. Male Hollywood celebrities were initially reluctant to be associated with the cause, considering the potential for rumors about their own sexuality or HIV status, but then Elizabeth Taylor, the last great movie star of Hollywood’s Golden Era, stepped forward, and in a very big way. Taylor was well aware of AIDS and was angry at the silence around it. “Bitch, do something yourself” is what she told herself, and she leaned in to become the figurehead of Hollywood’s AIDS activism and ‘Commitment to Life’ fundraising. At first a lone celebrity voice in AIDS fundraising, it took Rock Hudson’s shock death from AIDS in October 1985 at age 59 to galvanize the industry into action. The next dinner following his death drew a gauntlet of stars such as Cher, Burt Reynolds, Joan Rivers, and many more to the cause. Millions of dollars were raised. As well as their work helping the community, APLA, amongst other activists, had to fight various right-wing bigots who had ill intentions for the queer community. These included Lyndon Larouche who wanted to introduce quarantine rules for HIV positive people. Liz Taylor, in turn, increased her activism, becoming the spokesperson for another AIDS organization, AMFAR, and lobbied the US government at the highest level, including Ronald Reagan, who only mentioned the word AIDS for the first time in public in 1987.

their high percentage of queer employees, were particularly badly affected. APLA needed ever-increasing funds to deal with the avalanche of people requiring its support. The idea of a ‘Commitment to Life’ fundraising dinner was pitched to the movie industry. Male Hollywood celebrities were initially reluctant to be associated with the cause, considering the potential for rumors about their own sexuality or HIV status, but then Elizabeth Taylor, the last great movie star of Hollywood’s Golden Era, stepped forward, and in a very big way. Taylor was well aware of AIDS and was angry at the silence around it. “Bitch, do something yourself” is what she told herself, and she leaned in to become the figurehead of Hollywood’s AIDS activism and ‘Commitment to Life’ fundraising. At first a lone celebrity voice in AIDS fundraising, it took Rock Hudson’s shock death from AIDS in October 1985 at age 59 to galvanize the industry into action. The next dinner following his death drew a gauntlet of stars such as Cher, Burt Reynolds, Joan Rivers, and many more to the cause. Millions of dollars were raised. As well as their work helping the community, APLA, amongst other activists, had to fight various right-wing bigots who had ill intentions for the queer community. These included Lyndon Larouche who wanted to introduce quarantine rules for HIV positive people. Liz Taylor, in turn, increased her activism, becoming the spokesperson for another AIDS organization, AMFAR, and lobbied the US government at the highest level, including Ronald Reagan, who only mentioned the word AIDS for the first time in public in 1987.

Despite the initial success of organizations like APLA and AMFAR, it soon became clear that their services were largely being accessed by white people even though people of color (POC) were statistically far more likely to be dealing with the virus. Step forward the legendary Jewel Thais Williams, founder and owner of iconic LA black queer club Catch One. She realised her staff and customers were being decimated by the disease and were not being properly supported by the existing charities which were often many miles away in the more affluent white suburbs of LA. She started the Minority Aids Project to help her community and a similar project, Bienestar, co-founded by Oscar De La O, was set up for the Latino community.

Despite the initial success of organizations like APLA and AMFAR, it soon became clear that their services were largely being accessed by white people even though people of color (POC) were statistically far more likely to be dealing with the virus. Step forward the legendary Jewel Thais Williams, founder and owner of iconic LA black queer club Catch One. She realised her staff and customers were being decimated by the disease and were not being properly supported by the existing charities which were often many miles away in the more affluent white suburbs of LA. She started the Minority Aids Project to help her community and a similar project, Bienestar, co-founded by Oscar De La O, was set up for the Latino community.

More and more AIDS charities and activist groups were launched nationwide, including Larry Kramer’s ACT UP in New York. The joyful Commitment to Life AIDS fund-raising dinners drew in the elite from the worlds of film, TV, and fashion. Liz Taylor, along with people like Bette Midler, Madonna, Elton John, Liza Minelli, George Michael, Whitney Houston, Barbra Streisand, and countless more, helped raise millions, and together with local queer activists and rich donors such as David Geffen and Barry Diller, piled pressure on the US government to act. This did speed up the launch of AZT, the first drug launched in 1987, to help deal with AIDS symptoms, albeit with nasty side effects for many users.

By 1992, 170,000 people had died of AIDS in the US, often painful, harrowing deaths. Many died alone. Homophobia was rife, especially outside the creative industries. Opinions in the US then slowly began to change, firstly as the result of more and more people defiantly coming out. Secondly, HIV awareness campaigns re the spread of the virus began to relax people who realized they couldn’t just catch the virus by being near someone with it. The 1993 film Philadelphia, starring Tom Hanks, also helped change opinions, as did MTV’s 1994 series The Real World, starring the handsome Pedro Zamora, who was living with HIV. The basketball player Magic Johnson admitted that he was living with HIV, and that did a lot to raise awareness of the virus in the black community.

In 1995, combination therapy of protease inhibitors was introduced. This daily combination of pills meant that most HIV-positive people could reduce their HIV viral loads to undetectable, allowing their immune systems to recover from the damage done by the virus, and to lead pretty normal lives. AIDS deaths quickly dropped by half, and nowadays are a tiny fraction of what they were back then.

To date, 36 million people have died of AIDS globally. Another 40 million are living with the HIV virus, including one million in the US. 25% of those living with HIV globally, however, have no access to HIV medication.

Schwarz’s documentary is the most comprehensive film on the history of AIDS within a community. He details the fight by an intrepid group of people living with HIV/AIDS, doctors, movie stars, studio moguls, and activists to change the course of the epidemic. He combines often harrowing archive footage and imagery with interviews with those who were there at the time to tell amazing stories of endurance and survival. Everyone should watch this powerful film about an important period in queer history, especially those unaware of the prior horrors of AIDS.

P.S. The film is currently playing the LGBTQ+ Film Fest circuit: next up FILM OUT SAN DIEGO

for future screenings www.automatpictures.com

Queerguru’s Contributing Editor Ris Fatah is a successful fashion/luxury business consultant (when he can be bothered) who divides and wastes his time between London and Ibiza. He is a lover of all things queer, feminist, and human rights in general. @ris.fatah